What does the expenditure on homelessness tell us about the our approach to tackling homelessness?

Author: Mike Allen

Despite its technical title, the Focus on Homelessness report “Public Expenditure on Services for Households Experiencing Homelessness” (March 2025), paints a vivid picture of how we have responded to the enduring homelessness crisis over the last decade. The picture it paints is not one driven by vision or ideology, but rather a reactive response which constantly underestimates the scale of the challenge and consumes resources trying to contain, rather than solve, the problem. It also provides hints about what we could do better.

Since it was set up 40 years ago, one of Focus Ireland’s core contributions to tackling homelessness has been a commitment to independent and challenging research. There has been a strong commitment to finding out the reality of what causes homelessness, what people experience while homeless and what can solve it. The Focus Ireland research and evaluation series is full of findings which were uncomfortable, not only for policy makers but also sometimes for ourselves.

The ‘Focus on Homelessness’ series, produced with the School of Social Work and Social Policy in Trinity College, is on the extreme edge of that tradition, with a robust editorial policy of setting out data from official sources without comment or interpretation. Prof O’Sullivan’s careful work in turning a decade of individual reports into time series tells its own story.

This blog provides Focus Ireland’s analysis, drawing attention to some of the findings in the report which we think are significant, and putting forward ideas which we believe would produce better outcomes.

Most of the increase goes to private ‘for-profit’ providers

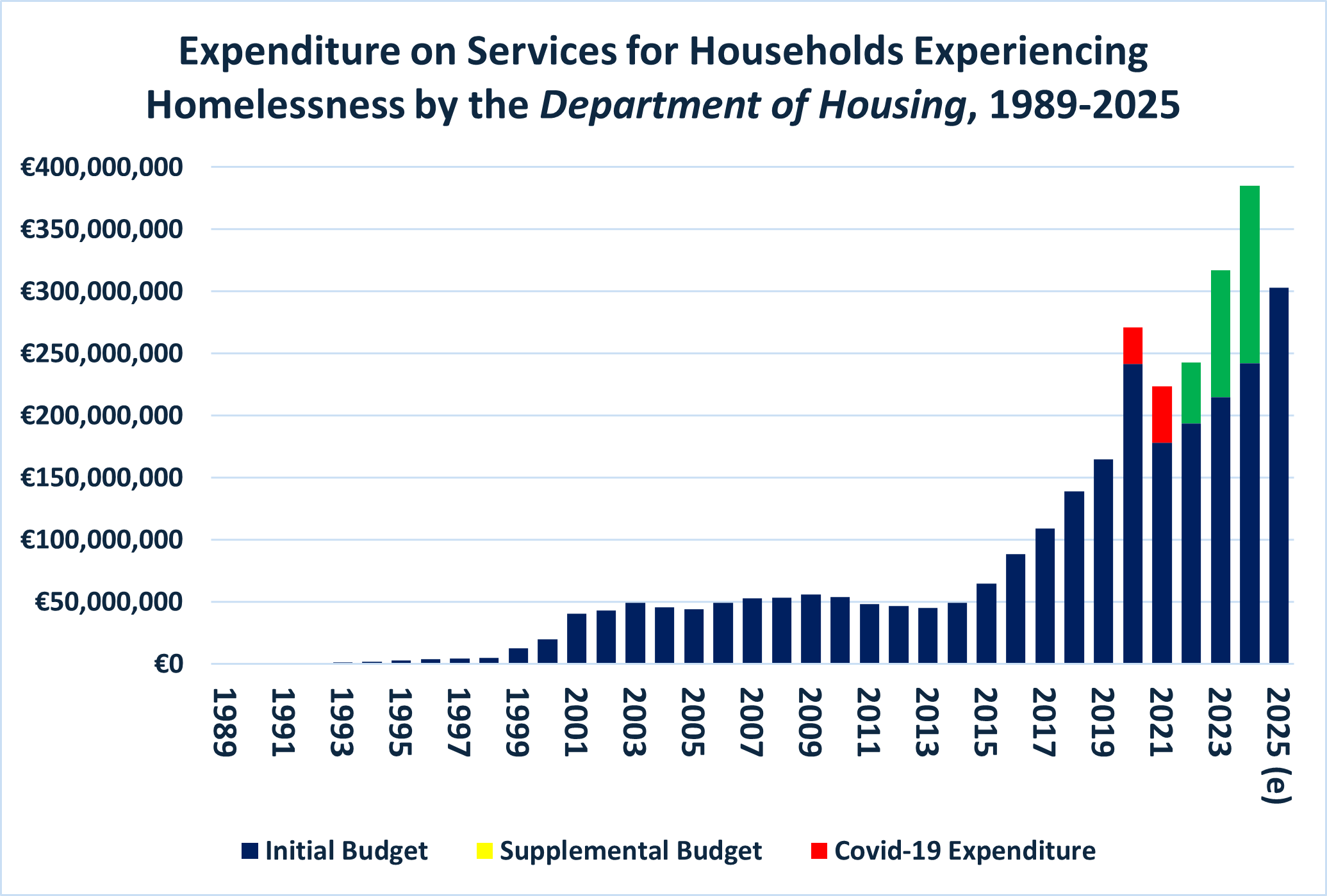

The most obvious, but necessary, thing to say about the report is that we are spending an ever-increasing amount of money on an ever-increasing problem. Over the dozen years covered, homelessness grew from just over 3,000 to just over 15,00o. With such dramatic increases, percentages can be a bit overwhelming: this is an increase of 400% nonetheless.

To meet this growing problem, local authority spending on homelessness, from all sources, (Fig. 1) grew from some €73.5m to €531m – over 600%.

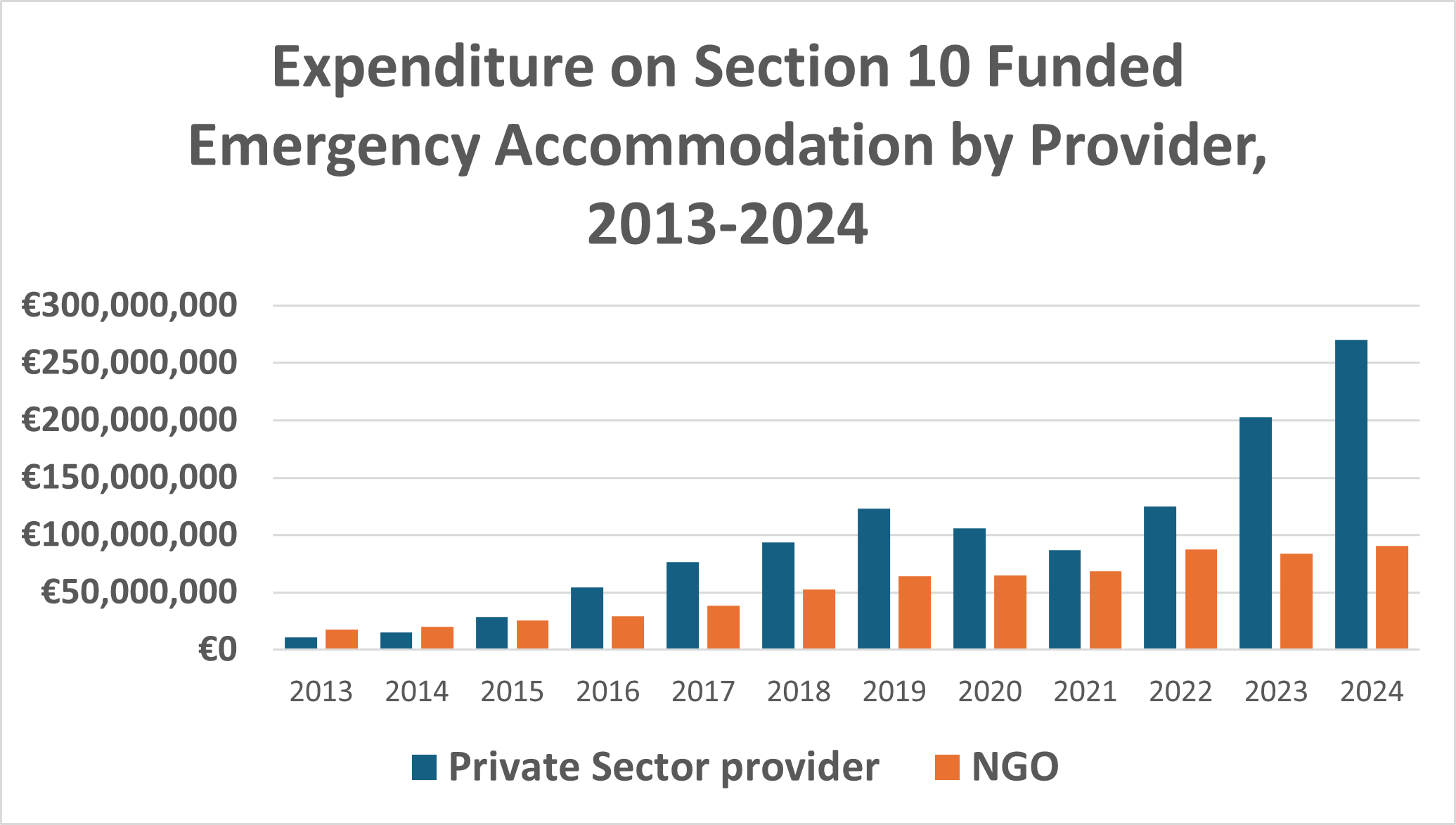

The fact that the increase in expenditure outstrips even the increase in the number of people who are homeless is concerning, but the upward direction of spending not itself surprising. What should be surprising, given the way that the response to homelessness tends to be discussed, is who is being paid from this increased spending. When people think of organisations supporting people who are homeless, they think of the NGOs or Charities which have traditionally worked in the area.

The report shows that you have to go back before more than a decade to find a time when the not-for-profit charitable sector was the major provider of services. Since then, the private for-profit sector has been the larger player. As the overall budget has grown, for-profit organizations have absorbed an increasing proportion so that in 2024, for every euro provided to not-for-profit organisations, three euros went to for-profit private companies. Of every €10 spent on tackling homelessness €7.50 now goes to for-profit organisations.

Why the shift to ‘for profit’ providers?

It would be easy to characterize this as ‘privatisation’ of the homeless sector, and put it in a category of Government policies which have favoured market-based response and private enterprise over the last number of decades. The reality is, perhaps, even more worrying. This shift of resources from non-profit charities to for-profit private companies appears to be not the outcome of deliberate Government policy, but rather a function of the absence of, or the failure of, policy.

Given the sums involved it is worth looking at the key factors pushing this dramatic shift towards for-profit providers.

A European Observatory on Homelessness Report on the increased role of private sector organisations in providing homeless services identified a process in several countries in which ‘overflow accommodation’ which was contracted from the private sector in response to what were seen as short term issues was absorbed into mainstream provision – and budgets – as the ‘short-term’ issues persisted. This has clearly been a repeated process in Ireland – the Rebuilding Ireland promise to end the use of hotels morphing into a commissioning process in which former hotels became contracted into dedicate emergency homeless accommodation being perhaps the most well known.

A second factor has been the capacity of not-for profit homeless organisations to grow to provide the increased beds. The sudden increase in demand for more emergency accommodation came from the mid-2010s, at a time when NGO homeless providers wanted to move away from basic emergency accommodation as a response to homelessness. They wanted to move into housing led and Housing First solutions, and where they provided hostels they wanted them to be of a higher quality with a skilled staff who would support people to move out of homelessness. In principle, Government policy also supported this shift, but in reality, with rapidly rising homeless numbers, local government needed more beds quickly and, as we have seen, only for as long as the temporary increase required. Homeless NGOs also felt that the funding available was insufficient to run the level of service that they felt was required, and many also had reservations about their own sustainability if they grew their hostel accommodation too rapidly. For-profit providers, on the other hand, who provide accommodation only, without supports, were able to react quickly, meeting the minimum standards required by Government. The one homeless NGO which grew rapidly to provide these beds was the Peter McVerry Trust.

It is worth noting that over the decade covered in the report, while this transformation in who was providing shelter for people who are homeless was taking place, the only public discussion of the issue has been about whether there were ‘too many homeless charities’ and whether they were too big. The growth in private for-profit provision has largely gone unremarked.

It is important to note that we are not suggesting that the provision of homeless services by private companies is intrinsically wrong. While there would be some public aversion to people making profit in such circumstances, the reality of our system is that all our social and health services working with disadvantage people include some element of private for-profit provision. There is no reason, in principle, that homeless services would be any different. The significant issue here is that private companies only provide shelter, and while shelter is essential, it makes no contribution to lasting solutions. This is discussed in more detail below.

What are we spending the money on.

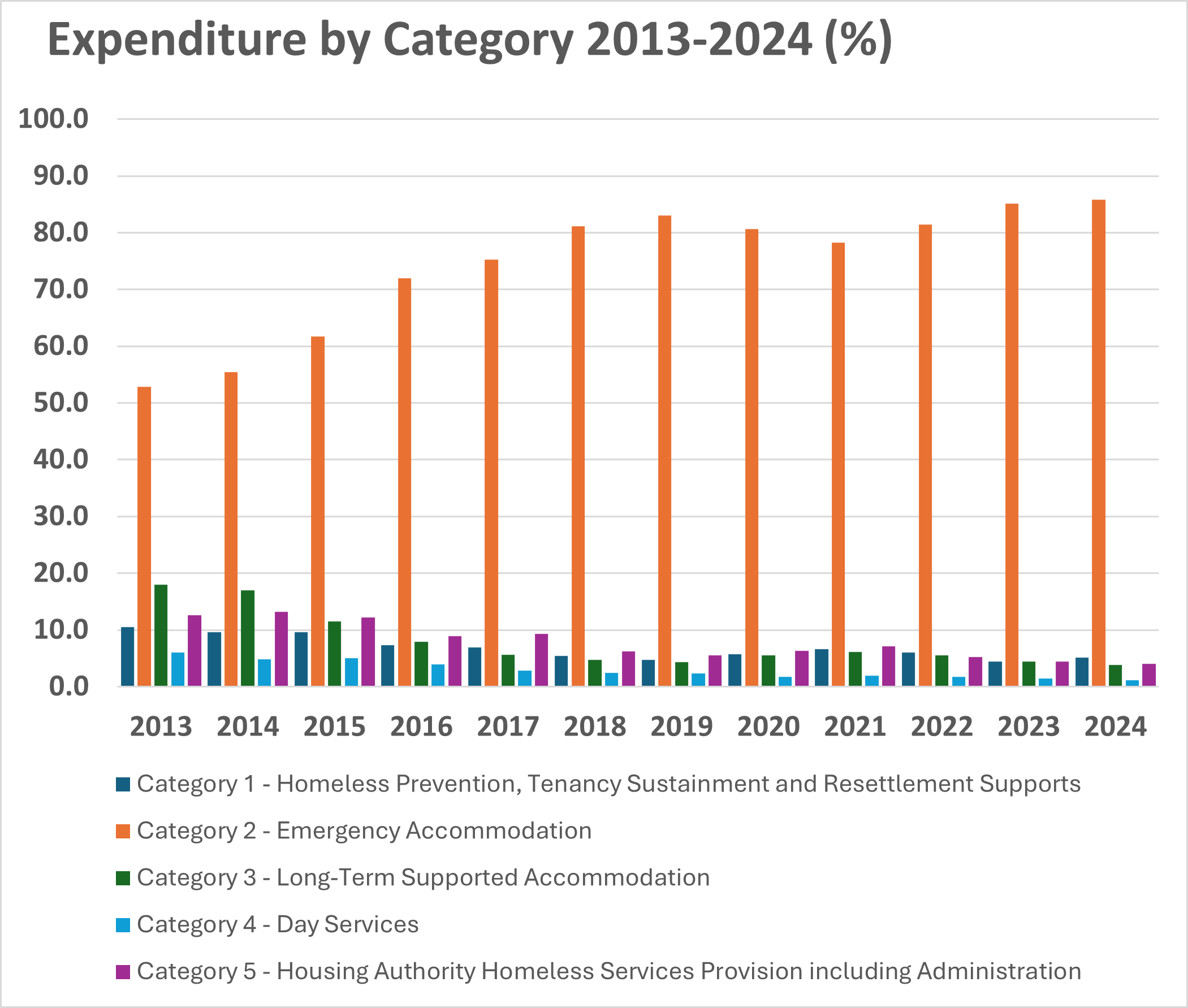

The final factor driving this increase reliance on the private rental sector relates to what the state has been spending its money on. Even from the earliest data available, the overwhelming proportion of expenditure went on providing emergency homeless accommodation. At the start of the period around half of expenditure was on emergency accommodation. In 2024, emergency accommodation accounted for 86% of all homeless related spending – amounting to €361 million.

Providing emergency shelter is, of course, enormously important. It provides a humanitarian response and ensures that people who are homeless are not forced to be ‘roofless’, to sleep rough, which the most extreme – and morally repugnant – form of homelessness.

The problem with providing emergency shelter is that it does nothing to address the underlying issues. The difficulties that a person faces in the evening when they go into the homeless shelter remain unchanged when they wake to face another day.

Providing shelter does not change the underlying circumstances of the person or family in society. The shelter we gave yesterday has to be provided again today and again tomorrow.

This is not because these things cannot be changed, some of the other categories of Section 10 expenditure – prevention, tenancy sustainment, long-term accommodation – can actually change the underlying circumstance and, in many cases, provide lasting solutions.

In other areas of social policy, and in particular labour market policy, the two types of intervention are called ‘active’ and ‘passive’ measures. Before the turn of the century, long-term unemployment was seen as the dominant social problem and there were enormous, co-ordinated efforts to tackle it across the EU and in Ireland. These policies were to a large extent successful and had at their core a determination to shift resources from passive measures and towards active measures – like, in this case, training, employment services etc. If we think of how we deploy our homeless resources in these terms, we can begin to understand why putting so much of our effort in passive supports has achieved so little.

Of course, the most important active support for people who are homeless is the provision of affordable housing, as a first step in understanding this. However, while we believe provision of sufficient social housing is in itself a good thing, we can only really count social housing provision as an ‘active homeless measure’ to the extent that households that are homeless are at risk of homeless actually benefit from it. There is some recognition of this in ‘Securing our Future’ the Government’s Programme for Government, at least for families (p44) but there have been as yet no measures to turn this into action.

This ‘active/passive’ analysis of funding, should also help us to think of homelessness as a dynamic problem. There is tendency to look at the increase in homelessness as a sort of building up. As if the over 10,000 adults who are homeless today comprise the 8,000 who were homeless two years ago plus all those who have become homeless since. In actual fact, over the period since 2014, a total of over 60,000 adults have gone through homeless services for at least one night. In other words, the expenditure over this period needs to be seen as supporting over 60,000 adults out of homelessness as well as the 10,600 who are currently homeless.

One of the relatively few good news stories in Irish homelessness is the extent to which successive Governments have adopted Housing First, set out a national strategy for its implementation and established a national office to support it. There are, of course, areas where we could do better – better integration of health supports, applying its lessons to families and young people, and of course access to suitable housing – but none of this should detract from the progress made with this effective approach.

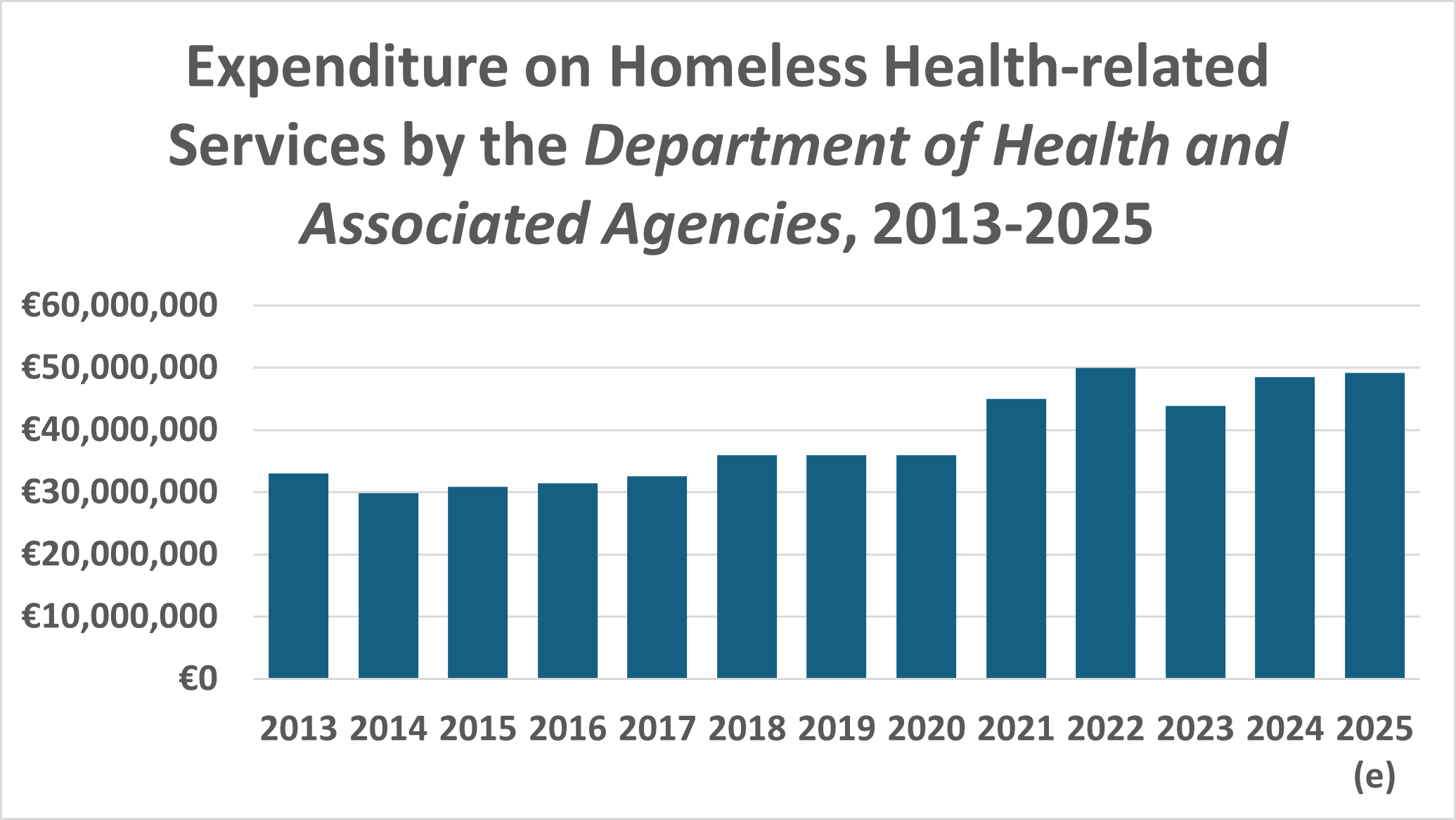

Housing First expenditure is included in Category 1 (Homeless Prevention) (Fig. 4) and is one of the reasons for the welcome growth in this category from €5.7 million in 2013 to €21.4 million in 2024, nevertheless it has decreased as a percentage of expenditure from 10% in 2013 to 5% in 2024. While no breakdown is available, the growth of Housing First must be one of the key drivers of the increase in Health expenditure on homelessness from €33m in 2013 to €48.6m by 2024 (Fig. 3).

Health Expenditure does not respond to the growing crisis

This graph on Health Expenditure (Fig. 3) is easily overlooked. While the graph for Section 10 expenditure demands attention with its rapid upward curve, the graph for health, with its modest slope, can slip past.

But this would miss an important question – how can it be, when the number of men, women and children who are homeless has gone up by 400%, the funding for health supports has increase by less than 50%? In 2013, for each person who was in emergency homeless accommodation we were spending around €10,000 on health supports, while today we are spending just €3,200. Of course, the calculation is simplistic: there are many people who are not included in the Section 10 homeless figures who receive services from homeless related health services, and, more significantly, many people who are homeless benefit from mainstream health services not shown in this graph. But this makes the question even starker: the biggest growth in health expenditure on homelessness has been the successful Housing First programme and Housing First tenants are, quite rightly, not included in the 15,000 homeless counts. While detailed breakdowns are not available, it would appear that around the same health funding is available to the 15,000 people now in emergency accommodation as was provided to 3,000 people a decade ago.

The health services referred to here are addiction and mental health services which are essential for a significant number of people who are homeless and are critical in ending a cycle of between detox and homelessness. When combined with housing in housing led initiatives, health services are essential ‘active’ measures which can sustain exits from homelessness. The Housing Commission drew attention to this challenge (p 205 Recommendation 68), recommending not just a dedicated budget line for support services for homeless people but also integration of health and housing supports.

Conclusion

The series of graphs in the report paints a picture of reactive response to homelessness, repeatedly underestimating the scale of the problem, repeatedly taking short-term measures and then incorporating them into the mainstream, taken up with managing the latest unpredicted surge, drawing on ever increasing resources but unable to direct attention or resources at solutions.

Some of this is simply due to external factors: the long-run impact of the financial crisis, the scale of the problem bearing down each month on highly committed and hard-working public officials struggling to get ahead of it. But some of it is due to factors which are within Government control. Perhaps the most striking of these is set out in Fig 2 – where the most recent columns show a persistent under-provision of funding in the annual budget announced in October each year. Focus Ireland set out our detailed concerns about this in our 2024 Budget Submission and since. Aside from the catastrophic consequences that will arise if there were not available funds for the supplementary budget at the end of the year, this is almost a text-book example of how to ensure that a crisis is met reactively and without planning. Entirely predictable challenges become ‘unforeseen’, the system dealing with the crisis is itself in perpetual crisis mode and nobody is looking beyond the next wave.

The appointment of a new Minister, James Browne, and the Programme for Government commitment to “a new fully funded, radical and realistic housing plan to get more homes built” to replace Housing For All provides an opportunity to address some of these challenges. The continued commitment to the Lisbon Declaration to ‘work towards ending homelessness by 2030’ is also welcome, less so the continued silence on what sort of progress we should expect or how we will achieve. Perhaps the most potentially impactful commitment is to “Ensure a holistic, cross departmental approach to homelessness prevention.” What action emerges from this will be of vital importance. Prevention is only one dimension of an ‘active measures’ approach to homelessness (the other being exits), but it would be a start. As discussed in our previous blog post, pressing ahead with proposed cuts to the Tenant-in-situ scheme, one of the most successful homeless prevention measures, without consultation, and driven by short-sighted funding targets, is not the best place to start.